【重磅研究】杨原:大国政治的喜剧 ——两极体系下超级大国彼此结盟之谜

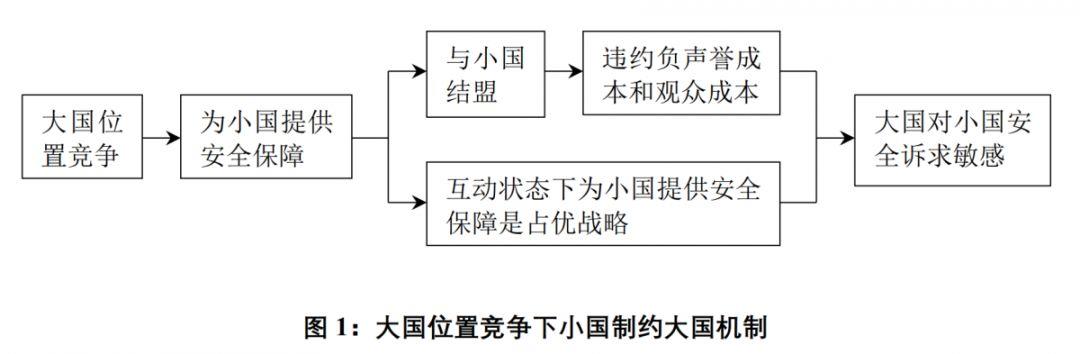

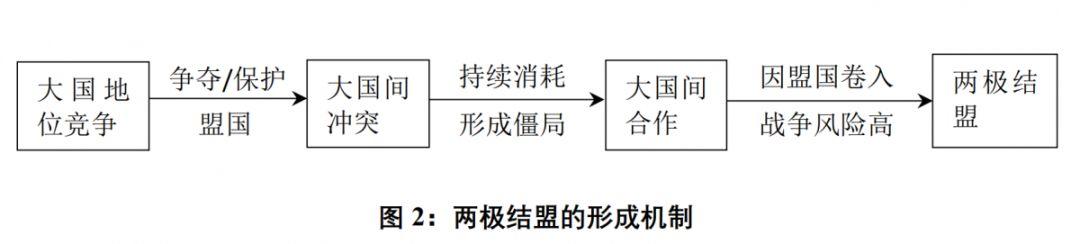

国际体系中实力最强的两个国家最易出现冲突和战争,两极体系下两个一级大国会持续对抗,这是所有现实主义理论乃至大部分主流国际安全理论的基本共识。然而在古希腊城邦时期和中国春秋时期的两极体系中,却出现了两“极”彼此结盟这种最高程度的合作行为。现有的合作理论和联盟形成理论均难以解释这种“两极结盟”现象。为解释这种反常现象,本文提出了大国竞争的“权力大/小”悖论和广义“稳定/不稳定”悖论,并以此为基础,揭示了两极体系下大国从冲突到结盟的具体机制。两极体系下大国为竞争更高的权力地位,容易受小国牵连而陷入冲突和战争。如果这种冲突陷入了“消耗战”并形成僵局,停止对抗就将成为双方的共同选择。如果此时大国因小国而再次陷入双输性对抗的风险依然显著,那么以结盟这种方式向小国释放信号,表达无意因小国而继续对抗的决心从而规避进一步的损失,将成为两个大国的均衡选择。“两极结盟”研究有助于拓展学界对联盟起源、两极体系性质、大国权力竞争等重要理论议题的理解,也为中美冲突管控前景提供了新的思考视角。

【关键词】大国权力竞争;古代国际关系;联盟理论;两极体系;修昔底德陷阱

。

。问题的提出

[1] 关于古希腊城邦体系的雅典斯巴达两极结构,参见Peter J. Fliess, Thucydides and the Politics of Bipolarity, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1966; Robert Gilpin, “Peloponnesian War and Cold War,” in Richard Ned Lebow and Barry S. Strauss eds., Hegemonic Rivalry: From Thucydides to the Nuclear Age, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1991, pp.31-49; Carlo M. Santoro, “Bipolarity and War: What Makes the Difference?” in Richard Ned Lebow and Barry S. Strauss eds., Hegemonic Rivalry, pp.71-83。关于春秋体系的晋楚两极结构,公元前546年弭兵之会的决议本身就是当时晋楚两国权力地位的很好体现:除齐、秦两国外,其他国家均须同时向晋、楚两国朝贡。与会各国对此均无异议,这反映了当时各国对晋、楚两国所享有的超越其他国家的权力地位的一种共识:“晋、楚狎主诸侯之盟也久矣”。参见《左传·鲁襄公二十七年》,载李宗侗注译、叶庆炳校订:《春秋左传今注今译》,北京:新世界出版社2012年版,第855—859页。历史学家也指出,晋楚两国的历史构成了春秋史的中坚。参见顾德融、朱顺龙:《春秋史》,上海:上海人民出版社2003年版,第162页。

[2] 公元前421年,古希腊喜剧作家阿里斯托芬专门就签订《尼基阿斯和约》一事创作了一出名为Peace的喜剧。John Zumbrunnen, Aristophanic Comedy and the Challenge of Democratic Citizenship, Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2012, p.23. 这从一个侧面反映出,不管伯罗奔尼撒战争此后的进程如何,至少在公元前421年,雅典和斯巴达的停战和结盟被当时的人们视为是大国政治的一个喜剧。

[3]Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, ed. and trans. by Jeremy Mynott, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 5.23.1-2, p.336.

[4] 《左传·鲁成公十二年》,《左传·鲁襄公二十七年》,第602、856页。

[5] 经典且有代表性的定义参见Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliance, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987, p.12; Glenn H. Snyder, “Alliance Theory: A Neorealist First Cut,” Journal of International Affairs, Vol.44, No.1, 1990, p.104; Brett Ashley Leeds, et al., “Alliance Treaty Obligations and Provisions: 1815-1944,” International Interactions, Vol.68, No.3, 2002, p.238。

[6] Joseph Lepgold, “Is Anyone Listening? International Relations Theory and the Problem of Policy Relevance,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol.113, No.1, 1998, pp.47-50.

[7] 例如,兰德尔·施维勒对第二次世界大战起因的研究、许田波对中国战国时期由无政府状态走向统一帝国原因的研究、康灿雄对近代早期东亚朝贡体系和平属性的研究,其研究对象均是罕见的或难以重现的,而这些从特殊性而非一般性角度开展的困惑导向型研究的价值显然是无可否认的。参见Randall Schweller, Deadly Imbalances: Tripolarity and Hitler’s Strategy of World Conquest, New York: Columbia University Press, 1998; Victoria Tin-bor Hui, War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005; David C. Kang, East Asia before the West: Five Centuries of Trade and Tribute, New York: Columbia University Press, 2010。

[8] Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics, Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1979, p.168.

[9] 对“polarity”的界定包含了客观和主观两方面的内容。从客观角度对两极结构的操作化界定,参见David P. Rapkin, William R. Thompson and Jon A. Christopherson, “Bipolarity and Bipolarization in the Cold War Era: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Validation,” The Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol.23, No.2, 1979, pp.261-295; William R. Thompson, “Polarity, the Long Cycle, and Global Power Warfare,” The Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol.30, No.4, 1986, pp.587-615。对“polarity”主观内容的界定,参见Benjamin Zala, “Polarity Analysis and Collective Perceptions of Power: The Need for a New Approach,” Journal of Global Security Studies, Vol.2, No.1, 2017, pp.2-17。

[10] Arvind Subramanian, “The Inevitable Superpower: Why China’s Dominance Is a Sure Thing?” Foreign Affairs, Vol.90, No.5, 2011, pp.66-78; James Dobbins, “War with China,” Survival, Vol.54, No.4, 2012, pp.7-24; Minxin Pei, “The Loneliest Superpower: How did China End up with Only Rogue States as Its Real Friends?” Foreign Policy, March 20, 2012, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/03/20/the_loneliest_superpower; Yuan Yang, “Escape both the ‘Thucydides Trap’ and the ‘Churchill Trap’: Finding a Third Type of Great Power Relations under the Bipolar System,” Chinese Journal of International Politics, Vol.11, No.2, 2018, pp.193-235;阎学通:《历史的惯性:未来十年的中国与世界》,北京:中信出版社2013年版。

[11] Stephen G. Brooks, William C. Wohlforth, “The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers in the Twenty-first Century: China’s Rise and the Fate of America’s Global Position,” International Security, Vol.40, No.3, 2015/2016, pp.7-53.

[12] John J. Mearsheimer, “The Gathering Storm: China’s Challenge to U.S. Power in Asia,” Chinese Journal of International Politics, Vol.3, No.4, 2010, pp.381–396; Aaron L. Friedberg, A Contest for Supremacy: China, America, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2011.

[13] 参见Randall L. Schweller, “Tripolarity and the Second World War,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol.37, No.1, 1993, p.75; Raimo Vayrynen, “Introduction,” in Raimo Vayrynen ed., The Waning of Major War, London: Routledge, 2006, p.13; Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, World out of Balance: International Relations and the Challenge of American Primacy, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008, p.29。

[14] 华尔兹就是在这个意义上使用“大国”一词。Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics, p.162.

[15] 有研究显示,“两极结构”与“霸权”不矛盾,两极体系中也可能存在霸权国(当然也就有可能存在崛起国)。Thomas J. Volgy and Lawrence E. Imwalle, “Hegemonic and Bipolar Perspectives on the New World Order,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol.39, No.4, 1995, pp.819-834.

[16] A. F. K. Organsky, World Politics, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1958; A. F. K. Organsky and Jacek Kugler, The War Ledger, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980.

[17] Robert Gilpin, “The Theory of Hegemonic War,” in Robert I. Rotberg and Theodore K. Rabb, eds., The Origin and Prevention of Major War, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp.15-37.

[18] John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

[19] Graham Allison, “The Thucydides Trap,” in Richard N. Rosecrance and Steven E. Miller eds., The Next Great War? The Roots of World War I and the Risk of U.S.-China Conflict, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2014, pp.73-79.

[20] Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Stability of a Bipolar World,” Daedalus, Vol.93, No.3, 1964, pp.881-882.

[21] Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics, p. 170; Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Stability of a Bipolar World,” pp.882-883.

[22] Michael Brecher and Wilkenfeld Jonathan, Crises in the Twentieth Century, Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1987, quoted from Thomas J. Volgy and Lawrence E. Imwalle, “Hegemonic and Bipolar Perspectives on the New World Order,” p.826.

[23] 有关两极稳定论的争论和批判参见Michael Haas, “International Subsystems: Stability and Polarity,” The American Political Science Review, Vol.64, No.1, 1970, pp.98-123; Patrick James and Michael Brecher, “Stability and Polarity: New Paths for Inquiry,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol.25, No.1, 1988, pp.31-42; Dale C. Copeland, “Neorealism and the Myth of Bipolar Stability: Toward a New Dynamic Realist Theory of Major War,” Security Studies, Vol.5, No.3, 1995, pp.29-89; Randolph M. Siverson and Michael D. Ward, “The Long Peace: A Reconsideration,” International Organization, Vol.56, No.3, 2002, pp.679-691。

[24] Arthur A. Stein, Why Nations Cooperate, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990, p. 151.

[25] Hans J. Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948; Richard Ned Lebow, A Cultural Theory of International Relations, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

[26] Robert Powell, “Absolute and Relative Gains in International Relations Theory,” American Political Science Review, Vol.85, No.4, 1991, pp.1303-1320.

[27] John H. Herz, “Idealist Internationalism and the Security Dilemma,” World Politics, Vol.2, No.2, 1950, pp.157-180; Robert Jervis, “Cooperation under the Security Dilemma,” World Politics, Vol.30, No.2, 1978, pp.167-214.

[28] Mark Kramer, “Ideology and the Cold War,” Review of International Studies, Vol.25, No.4, 1999, pp.539-576.

[29] Andrew H. Kydd, Trust and Mistrust in International Relations, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2005; Charles L. Glaser, Rational Theory of International Politics, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2010; Shiping Tang, A Theory of Security Strategy for Our Time, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010; Charles A. Kupchan, How Enemies Becomes Friends, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

[30] 相似政体和意识形态对结盟的促进作用,参见Brett Ashley Leeds, “Domestic Political Institutions, Credible Commitments, and International Cooperation”, American Journal of Political Science, Vol.43, No.4, 1999, pp.979-1002; Dan Reiter and Brian Lai, “Democracy, Political Similarity, and International Alliances, 1816–1992,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol.44, No.2, 2000, pp.203-227; John M. Owen, IV, “When do Ideologies Produce Alliances? The Holy Roman Empire, 1517-1555,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol.49, No.1, 2005, pp.73-99。

[31] 有研究指出,古希腊城邦之间均存在一定的身份认同,形成了英国学派意义上的国际社会。参见Hans van Wees, “War and Peace in Ancient Greece,” in Anja V. Hartmann and Beatrice Heuser eds., War, Peace and World Orders in European History, London: Routledge, 2001, pp.33-38. 事实上,在春秋体系的诸侯国之间也在一定程度上存在类似的现象。但是,共同的身份认同作为一个常量,在两个案例中均并未能从一开始阻止竞争双方陷入战争。

[32] Bruce Russett and William Antholis, “The Imperfect Democratic Peace of Ancient Greece,” in Bruce Russett et al., Grasping the Democratic Peace: Principle for a Post-Cold War World, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993, pp.43-62.

[33] Stefan G. Chrissanthos, Warfare in the Ancient World: From the Bronze Age to the Fall of Rome,Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2008, p.50.

[34] 顾德融、朱顺龙:《春秋史》,第60页;黄朴民:《梦残干戈——春秋军事历史研究》,长沙:岳麓书社2013年版,第239页。

[35] Glenn H. Snyder, “The Security Dilemma in Alliance Politics,” World Politics, Vol.36, No.4, 1984, pp.461-495.

[36] Douglas M. Gibler, “The Costs of Reneging: Reputation and Alliance Formation,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol.52, No.3, 2008, pp.426–454; James D. Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests: Tying Hands versus Sinking Costs,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol.41, No.1, 1997, pp.68-90.

[37] Michael F. Altfeld, “The Decision to Ally: A Theory and Test,” Western Political Quarterly, Vol.37, No.4, 1984, p.526; James D. Morrow, “Arms versus Allies: Trade-offs in the Search for Security,” International Organization, Vol.47, No.2, 1993, p.208; Jesse C. Johnson, “The Cost of Security: Foreign Policy Concessions and Military Alliances,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol.52, No.5, 2015, pp.665–679.

[38] Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliance; Randall Schweller, “Bandwagoning for Profit: Bringing the Revisionist State Back In,” International Security, Vol.19, No.1, 1994, pp.72-107; Jesse C Johnson, “External Threat and Alliance Formation,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol.61, No.3, 2017, pp.736–745.

[39] Patricia A. Weitsman, Dangerous Alliances: Proponents of Peace, Weapons of War, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004; Jeremy Pressman, Warring Friends: Alliance Restraint in International Politics, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2008; Victor Cha, Powerplay: The Origins of the American Alliance System in Asia, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

[40] Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, New York: Viking Penguin, 2003, pp. 188, 199-200; Robin Seager, “After the Peace of Nicias: Diplomacy and Policy, 421-416 B.C.,” The Classical Quarterly, Vol.26, No.2, 1976, p.251.

[41] 有学者总结了古希腊城邦结盟的各种可能的原因,包括共同的文化传统、来自波斯的共同威胁、来自另一个同盟的威胁以及被迫在两个敌对势力之间选边的压力。这些原因显然均难以解释公元前421年雅典和斯巴达的这次结盟。参见Panayiotis P. Mavrommatis, “City-States and Alliances in Ancient Greece: Underlying Reasons of Their Existence and Their Consequences,” manuscript, December 8, 2004, https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/history/21h-301-the-ancient-world-greece-fall-2004/assignments/final.pdf。

[42] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 5.89, p.380.

[43] 理查德·勒博将国家间冲突的动因划分为恐惧、欲望和荣誉三类,参见Richard Ned Lebow, A Cultural Theory of International Relations。“冲突”与“竞争”存在微妙的差异,后者强调对新增利益的争夺。由“恐惧”所引发的冲突更多地是为了已有资源的安全,而对“欲望”和“荣誉”的追求则涉及新增的利益,因此后两者是“竞争”而不是笼统的“冲突”的主要动因。

[44] 相关梳理和探讨参见Paul K. Huth, “Territory: Why are Territorial Disputes between States a Central Cause of International Conflict?” in John A. Vasquez ed., What Do We Know about War, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000, pp.85-110; Monica Duffy Toft, “Territory and War,” Journal of Peace Research, Vol.51, No.2, 2014, pp.185-198; Dominic D. P. Johnson, Monica Duffy Toft, “Grounds for War: The Evolution of Territorial Conflict,” International Security, Vol.38, No.3, 2013/2014, pp.7-38。

[45] 有关演化生物学对地位动机的研究参见Roger D. Masters, “The Biological Nature of the State,” World Politics, Vol.35, No.2, 1983, pp.161–193; Bradley A. Thayer, “Bringing in Darwin: Evolutionary Theory, Realism, and International Politics,” International Security, Vol.25, No.2, 2000, pp.124-151; Arthur J. Robson, “Evolution and Human Nature,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol.16, No.2, 2002, pp.89-106。

[46] Richard Ned Lebow, A Cultural Theory of International Relations; T. V. Paul, Deborah Welch Larson, and William C. Wohlforth eds., Status in World Politics, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014; Steven Michael Ward, “Lost in Translation: Social Identity Theory and the Study of Status in World Politics,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol.61, No.4, 2017, pp.821-834; Andrew Q. Greve & Jack S. Levy, “Power Transitions, Status Dissatisfaction, and War: The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895,” Security Studies, Vol.27, No.1, 2018, pp.148-178;宋伟:《联盟的起源:位置现实主义分析——以一战前英德联盟战略为例》,载《世界经济与政治论坛》2017年第1期,第18—37页。

[47] Michael P. Colaresi, Karen Rasler, William R. Thompson, Strategic Rivalries in World Politics: Position, Space and Conflict Escalation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007, chapter 6, 7.

[48] Michael P. Colaresi, Karen Rasler, William R. Thompson, Strategic Rivalries in World Politics, pp.155-156.

[49] 例如,史蒂芬·布鲁克斯等学者就曾提出过这一质疑。Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry, and William C. Wohlforth, “Don’t Come Home, America: The Case against Retrenchment,” International Security, Vol.37, No.3, 2012/2013, p.29.

[50]David A. Lake, Hierarchy in International Relations, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2009.

[51] Tongfi Kim, The Supply Side of Security: A Market Theory of Military Alliances, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016.

[52] Glenn H. Snyder, Alliance Politics, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1997.

[53] 分别参见Brett V. Benson, Constructing International Security: Alliances, Deterrence, and Moral Hazard, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012; Tongfi Kim, “Why Alliances Entangle but Seldom Entrap States,” Security Studies, Vol.20, No.3, 2011, pp.350–377; Keren Yarhi-Milo, Alexander Lanoszka, and Zack Cooper, “To Arm or to Ally? The Patron’s Dilemma and the Strategic Logic of Arms Transfers and Alliances,” International Security, Vol.41, No.2, 2016, pp.90–139;左希迎:《承诺难题与美国亚太联盟转型》,载《当代亚太》2015年第3期,第4—28页。

[54] James D. Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests,” pp.68-90; Douglas M. Gibler, “The Costs of Reneging,” pp.426–454; Mark J. C. Crescenzi et al., “Reliability, Reputation, and Alliance Formation,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol.56, No.2, 2012, pp.259–274; Gregory D. Miller, The Shadow of the Past: Reputation and Military Alliances before the First World War, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2012.

[55] 杨原:《大国无战争时代的大国权力竞争》,北京:中国社会科学出版社2017年版,第100—108页。

[56] Robert A. Dahl, “The Concept of Power,” Behavioral Science, Vol.2, No.3, 1957, pp.202-203.

[57] 尤其当大国被小国拖入的争端与大国自身的直接利益不符时,更是如此。

[58] Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1989, p.20; Charles L. Glaser, Analyzing Strategic Nuclear Policy, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1990, p.46; Scott D. Sagan and Kenneth Waltz, The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: A Debate Renewed, New York: W. W. Norton, 2003.

[59] Robert Powell, “Nuclear Brinkmanship, Limited War, and Military Power,” International Organization, Vol.69, No.3, 2015, p.596.

[60] Prajit K. Dutta, Strategies and Games: Theory and Practice, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999, pp.125-126.

[61] 有关消耗战博弈的详细分析,参见Drew Fudenberg, Jean Tirole, Game Theory, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991, pp.119-126。

[62] 关于僵局的详细分析,参见I. William Zartman, “Ripeness: The Hurting Stalemate and Beyond,” in Paul Stern and Daniel Druckman eds., International Conflict Resolution after the Cold War, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000, pp.225-246; Dean G. Pruitt and Sung Hee Kim, Social Conflict: Escalation, Stalemate, and Settlement, New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, 2004, pp.171-188。

[63] 在多极体系下,当两个大国的对抗有可能引发双输性僵局时,它们可以向其他大国求助,从而改变讨价还价的实力对比。比如第一次世界大战曾一度陷入“僵局”,但随着美国加入协约国一方,双方对战争结果的预期很快从僵局转变为协约国获胜。而在两极体系下,两个一级大国要想走出僵局,除了依靠自己和对方之外,别无其他有效途径。

[64] Robert Powell, “War as a Commitment Problem,” International Organization, Vol.60, No.1, 2006, pp.169-203.

[65] Alex Weisiger, Logics of War: Explanations for Limited and Unlimited Conflicts, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2013.

[66] Dan Reiter, How Wars End, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009, pp.22-50; Robert Powell, “Persistent Fighting and Shifting Power,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol.56, No.3, 2012, pp.620-637.

[67] Michael P. Colaresi, Karen Rasler, William R. Thompson, Strategic Rivalries in World Politics, p.211.

[68] 周方银:《消耗战博弈与媾和时机的选择》,载《国际政治科学》2007年第3期,第52—96页;Catherine C. Langlois and Jean-Pierre Langlois, “Should Rational States Really Bargain While They Fight?” unpublished manuscript, Georgetown University, Georgetown, Washington, DC, 2012.

[69] I. William Zartman, “Ripeness: The Hurting Stalemate and Beyond,” pp.225-246.

[70] 双方对彼此讨价还价能力和未来讨价还价能力变化的预期达成共识,是战争结束的必要条件。James D. D. Smith, Stopping Wars: Defining the Obstacles to Cease-fire, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1995, p.15.

[71] Branislav L. Slantchev, “The Principle of Convergence in Wartime Negotiations,” American Political Science Review, Vol.97, No.4, 2003, pp.621–632; Robert Powel, “Bargaining and Learning While Fighting,” American Journal of Political Science, Vol.48, No.2, 2004, pp.344–361; Alex Weisiger, “Learning from the Battlefield: Information, Domestic Politics, and Interstate War Duration,” International Organization, Vol.70, No.2, 2016, pp.347–375.

[72] 需要注意的是,仅仅是成本和风险超过收益,还不足以迫使大国放弃为小国提供安全保障。在竞争态势下,即使成本大于收益,只要能在亏损到达自己所能承受的极限之前先“拖垮”竞争对手迫使其退出竞争,大国即使“赔本”也仍会坚持。这类似于市场竞争中企业将商品价格压低到成本以下的“价格战”策略和倾销策略。

[73] 结盟行为本身是一种有成本的信号释放(costly signaling),通过结盟,可以传递出可置信的偏好和意图。James D. Morrow, “Alliances, Credibility, and Peacetime Costs,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol.38, No.2, 1994, pp.270–297; James D. Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests,” pp.68–90; James D. Morrow, “Alliances: Why Write Them Down?” Annual Review of Political Science, Vol.3, No.1, 2000, pp.63-83.

[74] C国可能不清楚此时A国国力的损耗程度,也可能清楚但与B国的矛盾尖锐,这两种情况下C国都有动机捆绑A国以增加自己应对B国时的筹码。

[75] Douglas M. Gibler, “The Costs of Reneging,” pp.426–454; Mark J. C. Crescenzi et al., “Reliability, Reputation, and Alliance Formation,” pp.259–274; Gregory D. Miller, The Shadow of the Past.

[76] 联盟的承诺作用参见Alastair Smith, “Alliance Formation and War,” International Studies Quarterly, Vol.39, No.4, 1995, pp.405-425; James D. Morrow, “The Strategic Setting of Choices: Signaling, Commitment, and Negotiation in International Politics,” in David A. Lake and Robert Powell eds., Strategic Choice and International Relations, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1999, pp.77-114。

[77] Michael F. Altfeld, “The Decision to Ally,” p.526.

[78] James D. Morrow, “Arms versus Allies,” p.208.

[79] 这意味着同时产生了“自缚手脚”(tying hand)和“沉没成本”(sunk cost)两种成本。James D. Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests,” pp.68–90.

[80] B与A结盟的预期收益,可以根据B与C谁是争端挑起方,更精确地划分为两种情况:一种是C是挑起方,主动与B寻衅。因为B在与C的冲突中是被动一方,因此此时B的首要目的是避战,而与A结盟就已经能够实现这一目的。另一种是B是挑起方,它有着更强的改变现状的动机,因此单纯与A结盟可能还不足以抵消其放弃对抗的机会成本,还需要增加某种新的机制以增加双方结盟的收益。这种区别体现在雅典—斯巴达、晋—楚结盟进程的细微差异中。详见案例研究部分的讨论。

[81] John M. Rothgeb, Jr., Defining Power: Influence and Force in the Contemporary International System, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993, pp.27-28.

[82] “权力大小”悖论体现了权力的相互性(reciprocity),参见David A. Baldwin, Power and International Relations: A Conceptual Approach, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2016, pp.79-80。

[83] Thomas Harrison, “The Greek World, 478–432,” in Konrad H. Kinzl ed., A Companion to the Classical Greek World, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2006, pp.511-517.

[84] Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, pp.3, 18-19.

[85] Peter J. Fliess, Thucydides and the Politics of Bipolarity; Robert Gilpin, “Peloponnesian War and Cold War,” pp.31-49; Carlo M. Santoro, “Bipolarity and War,” pp.71-83.

[86] W. R. Connor, “Polarization in Thucydides,” in Richard Ned Lebow and Barry S. Strauss eds., Hegemonic Rivalry, pp.54-57; Marta Sordi, “Scontro di Blocchi e Azione di Terze Forze Nello Scoppio della Guerra del Peloponneso,” in Richard Ned Lebow and Barry S. Strauss eds., Hegemonic Rivalry, pp.87-98.

[87] Robert Gilpin, “Peloponnesian War and Cold War,” p.48.

[88] W. R. Connor, “Polarization in Thucydides,” p.67; Mark V. Kauppi, “Contemporary International Relations Theory and the Peloponnesian War,” in Richard Ned Lebow and Barry S. Strauss eds., Hegemonic Rivalry, pp.108-109.

[89] 尽管在阿奇达姆斯战争期间,雅典和斯巴达均曾尝试与波斯取得联系,但并未获得实质性结果,双方都认为很难有理由说服波斯介入其战争。Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, pp.84, 154-155.

[90] W. R. Connor, “Polarization in Thucydides,” p.67; Mark V. Kauppi, “Contemporary International Relations Theory and the Peloponnesian War,” p.109.

[91] Richard Ned Lebow, “Thucydides, Power Transition Theory, and the Causes of War,” in Richard Ned Lebow and Barry S. Strauss eds., Hegemonic Rivalry, p.135.

[92] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981, p.27.

[93] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 1.23.6, p.16.

[94] Carlo M. Santoro, “Bipolarity and War,” pp.74-75; Marta Sordi, “Scontro di Blocchi e Azione di Terze Forze Nello Scoppio della Guerra del Peloponneso,” pp.87-98; Richard Ned Lebow, “Thucydides, Power Transition Theory and the Causes of War,” pp.125-165; Paul A. Rahe, “The Peace of Nicias,” in Williamson Murray and Jim Lacey eds., The Making of Peace: Rulers, States, and the aftermath of War, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp.33-59.

[95] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 1.35, 1.40, pp.23-24, 26-27.

[96] Richard Ned Lebow, “Thucydides, Power Transition Theory, and the Causes of War,” pp.128-129.

[97] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 1.44.1, p.29.

[98] Victor Alonso, “Peace and International Law in Ancient Greece,” in Kurt A. Raaflaub, ed., War and Peace in the Ancient World, Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007, p.216.

[99] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 1.45.1, p.29.

[100] Paul A. Rahe, “The Peace of Nicias,” p.51.

[101] Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, p.28.

[102] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 1.28, p.19.

[103] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 1.126-1.139, pp.73-83.

[104] Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, p.45.

[105] 这是古希腊世界内部战争的一个重要特征,参见Hans van Wees, “War and Peace in Ancient Greece,” p.41.

[106] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 1.71.4, p.43.

[107] G. E. M. de Ste. Croix, The Origins of the Peloponnesian War, London: Gerald Duckworth & Company Limited, 1972, p.60.

[108] Richard Ned Lebow, “Thucydides, Power Transition Theory, and the Causes of War,” p.131.

[109] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 1.71.7, p.44.

[110] W. G. Forrest, A History of Sparta, 950-192 B.C., New York: Norton, 1968, p.108, quoted from Richard Ned Lebow, “Thucydides, Power Transition Theory, and the Causes of War,” p.160.

[111] Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, p.51.

[112] Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, pp.51-52.

[113] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 2.65.7, p.130.

[114] Paul A. Rahe, “The Peace of Nicias,” p.61; Stefan G. Chrissanthos, Warfare in the Ancient World, p.52.

[115] Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, p.86.

[116] Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, p.104; Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 3.19.1, p.171.

[117] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.30.

[118] Paul A. Rahe, “The Peace of Nicias,” p.67.

[119] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 5.23.1-2, p.336.

[120] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.26; Robin Seager, “After the Peace of Nicias,” p.249.

[121] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p. 27; Robin Seager, “After the Peace of Nicias,” p.251.

[122] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.31.

[123] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.32.

[124] G. Busolt, Griechische Geschichte, III: 2, 1205, quoted from Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.27.

[125] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.27.

[126] E. Meyer, Forschungen zur alten Geschichte, II, 353, quoted from Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.27.另外参见Paul A. Rahe, “The Peace of Nicias,” p.68。

[127] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.27.

[128] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.28.另外参见Paul A. Rahe, “The Peace of Nicias,” p.69。

[129] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.30.

[130] Robin Seager, “After the Peace of Nicias,” p.252.

[131] Donald Kagan, The Archidamian War, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1974, pp.338-339.

[132] Robin Seager, “After the Peace of Nicias,” p.249.

[133]Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 5.17.2, p.332.

[134] Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, 5.35.3, p.344.

[135] Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition, p.24.

[136] Robin Seager, “After the Peace of Nicias,” pp.250, 254; Donald Kagan, “Corinthian Diplomacy after the Peace of Nicias,” The American Journal of Philology, Vol.81, No.3, 1960, p.291.

[137] Robin Seager, “After the Peace of Nicias,” p.250.

[138] 参见Richard Ned Lebow, “Thucydides, Power Transition Theory, and the Causes of War,” p.147。

[139] Simon Hornblower, The Greek World, 479-323 BC, New York: Routledge, 2011, p.166.

[140] Donald Kagan, The Peloponnesian War, p.16.

[141] Donald Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969, p.346.

[142] Robin Seager, “After the Peace of Nicias,” p.252.

[143] 对《尼基阿斯和约》后科林斯外交的详细分析,参见Donald Kagan, “Corinthian Diplomacy after the Peace of Nicias,” pp.291-310。

[144] 顾德融、朱顺龙:《春秋史》,第162页。

[145] 公元前546年第二次弭兵之会的决议本身是对当时晋、楚、齐、秦等大国权力地位的直接体现。此次会议达成的协议规定,除齐、秦两国外,其他国家均须同时向晋、楚两国朝贡。与会各国对此均无异议,这反映了当时各国对晋、楚两国所享有的超越其他国家的权力地位的一种共识,所谓“晋、楚狎主诸侯之盟也久矣”。参见《左传·鲁襄公二十七年》,第855—859页。

[146] 据据王日华和漆海霞的统计,在公元前769至公元前440年之间,受周王室直接分封建国的姬姓诸侯国彼此之间发生战争的频率和次数均显著低于姬姓诸侯国与非姬姓国家之间的战争。这说明在以血缘关系为基础的周朝分封体制内部,在中央权威的强制性力量已大为衰落的情况下,其所遗留的既有的政治秩序仍然在一段较长的时期内得到了相当程度的维持。王日华、漆海霞:《春秋战国时期国家间战争相关性统计分析》,载《国际政治研究》2013年第1期,第112、120页。

[147] 参见周方银:《松散等级体系下的合法性崛起——春秋时期“尊王”争霸策略分析》,载《世界经济与政治》2012年第6期,第9页。

[148] 《左传·鲁宣公十一年》,第490—491页。

[149] 杨宽:《战国史》,上海:上海人民出版社2003年版,第2页。

[150] 程远:《先秦战争观的发展》,载《西北大学学报(哲学社会科学版)》2008年第1期,第148页;杨宽:《战国史》,第2页。

[151] 《左传·鲁僖公二十七年》,第314页。

[152] 《左传·鲁僖公二十七年》,第314页。

[153] 《左传·鲁僖公二十八年》,第316—321页。

[154] 台湾三军大学编著:《中国历代战争史》(第1册),北京:中信出版社2012年版,第174页。

[155] 《左传·鲁僖公二十八年》,第322页。

[156] 《左传·鲁僖公二十八年》,第322页。

[157] 《左传·鲁僖公二十八年》,第323—324页。

[158] 《左传·鲁僖公二十八年》,第326—330页。

[159] 《左传·鲁宣公十二年》,第494页。

[160] 《左传·鲁宣公十二年》,第494—496页。

[161] 《左传·鲁宣公十二年》,第497页。

[162] 《左传·鲁宣公十二年》,第511页。

[163] 黄朴民:《梦残干戈》,第297页。

[164] 童书业:《春秋史》,上海:上海古籍出版社2010年版,第185—186页。

[165] 《左传·鲁成公十二年》,第602—603页。

[166] 《左传·鲁成公十六年》,第625页。

[167] 台湾三军大学编著:《中国历代战争史》(第1册),第244页。

[168] 《左传·鲁成公十六年》,第625页。

[169] 王庆成:《春秋时代的一次“弭兵会”》,载《江汉学报》1963年第11期,第41页。

[170] 《左传·鲁襄公九年》,第705页。

[171] 《左传·鲁襄公八年》,第697页。

[172] 《左传·鲁襄公二十七年》,第855页。

[173] 《左传·鲁襄公十年》,第719页。

[174] 黄朴民:《梦残干戈》,第345页。

[175] 《左传·鲁襄公二十七年》,第856—857页。

[176] 《左传·鲁襄公二十七年》,第859页。

[177] 黄朴民:《梦残干戈》,第348页。

[178] 黄朴民:《梦残干戈》,第349页。

[179] 有学者指出,“两极”这一术语从一开始就是与理解冷战的努力联系在一起的。R. Harrison Wagner, “What Was Bipolarity?” International Organization, Vol.47, No.1, 1993, p.79.

[180] 关于当前中美两极化不会重新引发冷战的讨论,见Yuan Yang, “Escape both the ‘Thucydides Trap’ and the ‘Churchill Trap’”; Odd Arne Westad, “Has a New Cold War Really Begun? Why the Term Shouldn’t Apply to Today’s Great-Power Tensions,” Foreign Affairs, March 27, 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-03-27/has-new-cold-war-really-begun.

【媒体国关】媒体变迁中的国关转向:国关文献中的新媒体研究现状 | 国政学人 第298期

【霸权研究】大国竞争战略中的经济遏制丨国政学人 第302期

【新刊速递】第10期 | International Studies Review, Volume.21, No.3, 2019

【新刊速递】第11期 | Cooperation and Conflict, Vol. 54, No. 4, 2019

【新刊速递】第12期 | International Affairs, Vol.95, No.6,2019

【新刊速递】第13期|Chinese Journal of International Politics, No.4, 2019

【新刊速递】第14期|Chinese Journal of International Politics, No.3, 2019

点“在看”给我一朵小黄花![]()

原文始发于微信公众号(国政学人):【重磅研究】杨原:大国政治的喜剧 ——两极体系下超级大国彼此结盟之谜